Between Silence and Utterance

Introduction

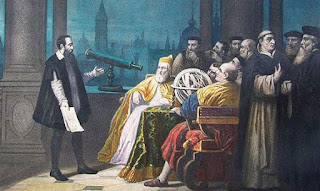

In an oft

ignored letter to the Grand Duchess of Tuscany in 1615,[1]

an Italian mathematician made the case, following the teaching of early Church

fathers like Tertullian, that God has been revealed to humanity in two books,

the book of nature and the book of scripture. Several decades earlier, the

Council of Trent, to push back against the rampant interpretive pluralism and

uncontrollable printing of the Protestant Reformers, had decreed that only

those scholars who were licensed by the Church were allowed to exegete

scripture – effectively preserving the professional authority of the Church’s

magisterium. Picking up on this move, this Italian thinker argued that God’s

other book of revelation, the book of nature, was written in a language that is

best understood and interpreted by professional mathematicians and those well

versed in natural philosophy. And so it was that Galileo Galilei became the

father of an approach to scientific discourse that could operate in its own

discrete sphere, without reference to the exegetical task of theology.

Bridge

The story we

typically hear about Galileo is the story of the heroic man of reason standing

up against the corrupt superstitions of the Catholic church. This story is tired,

cliched, and honestly not very accurate. Galileo was a man of his times.

Reflecting on the idea of the “two books” that the Christian tradition handed

on to him, Galileo’s contribution to the separation of theology from natural

philosophy is best understood as a natural outworking of the logic of professional

modes of control unleashed by Trent. Galileo, in this frame, is thus best

understood as contributing nuance to the unfolding concept of scientia. By scientia I mean, as the theologian T. F. Torrance has explained, any

form of inquiry that is fitting to its object of study. Galileo looks at the

two books of revelation, the book of nature and the book of scripture, and realizes

that to properly understand either of these objects of study, one must have a

fitting methodology. So, observing that Trent has established that the book of

scripture is to be understood according to the rules and linguistic expertise

of those officers of the magisterium who are rightly trained, he proposes that

to rightly interpret the book of nature, one must be skilled in the language of

that book. For Galileo, the language of the book of nature is mathematics, and

it is through the mastery of this language of mathematics that natural

philosophers can more perfectly interpret the book of nature and so, rightly

come to know its author.

For Galileo

then, there can be no contradiction between the cosmological claims of the

Bible and the findings of natural philosophy. Where the Bible does make such

claims, it does so in a linguistic register that is necessarily metaphorical,

for it does not attempt to use the proper language, that of mathematics, to

substantiate cosmological claims. Thus, Christians may, and indeed should,

insist that the earth revolves around the sun, and that these heavenly

movements can be expressed through the mathematical language of physics, and

not fear that biblical passages about the sun and moon being made to stand still

are rendered utterly meaningless.

The Two Books

Contrary to

many of his modernist biographers, Galileo is not merely using theological

traditions to beat the Catholic church at its own game in order to assure the

ultimate triumph of scientific knowledge. In fact, I would suggest that Galileo’s

attempt to secure the integrity of scientific inquiry arises from attention to

the pattern of divine self-disclosure we find in our psalm today.

Psalm 19

contains three linguistic moments. Verses 1-6 attend to the speech of creation

as the more general and chronologically prior revelation of God to the world. This

revelation is that which we have named earlier as “the book of nature.” The

second linguistic moment, verses 7-13 reflect on the perfection of the Law.

This is an ode to the second book, the “book of Scripture.” Both linguistic

moments are speech-acts of God, but for the final linguistic moment, it is us

who are given the chance to speak. Verse 14, a familiar enough prayer to those

of us who dare to preach is a reminder that our dogmatic pronouncements follow

from and are answerable to the Word that has been spoken in both creation and

scripture. One could read Galileo’s insistence on the distinct methodological

integrity of natural philosophy and theology to be his attempt to offer

acceptable language in response to these two books of revelation.

Two Books, One Story

I grew up

under a preacher who spent a lot of time talking about the reliability of the

Bible. Inevitably, at some point in his exceedingly lengthy sermons, he would

begin marching around the stage waving the Bible in the air, exhorting us to

trust and believe every word of it. I might have found that approach compelling

if he ever got around to telling us some of the content of that leather-bound

volume he swung about so ferociously. I don’t want to make the same mistake

this evening, droning on about the merits of the two books of revelation

without ever touching on the content of that revelation. So, holding lightly to

Galileo’s interpretive insights, lets turn to the psalm appointed for today.

Psalm 19 begins

with the lofty declaration,

“The heavens

are telling the glory of God;

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours forth speech,

and night to night declares knowledge.”

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours forth speech,

and night to night declares knowledge.”

This is

powerful imagery, and I know many Christians who claim an encounter with God

precisely in their contemplation of the created world, both scientific and

aesthetic. Indeed, one of the few “religious experiences” of my own life

happened while canoeing early in the morning on a lake in northern Manitoba. But

of course, as a good modern, I can never be sure if it was truly an encounter

with God’s glory or was merely an especially strong interpretation of events

guaranteed to me by my life-long formation as a Christian. Indeed, the psalm

itself is ambiguous about exactly who this god is that the heavens reveal. If

you have a Bible handy, notice how God is written in verse one compared to the name

given in verse seven. In verse one, we get the generic Semitic name for God, El,

but it tells us nothing about who or what that god is beyond its transcendent

divinity. Contrast this with the name given in verse seven – “The LORD.” Here

we have the covenant name for God in Old Testament idiom, the tetragrammaton,

the name spoken allowed only as Adonai or “The LORD.” And it is precisely here

that we see the diverging fields of reference for the two books of revelation.

While the book of nature can tell us, perhaps, that there is a divine being, or

at least a transcendent beyond, it gives us little clue as to the nature of

that being. Of course, verses five and six perhaps enable us to predicate some

qualities about this being; that it is powerful, and order giving, but these

predicates are almost universally assumed in our common definitions of deity.

The problem

with the book of nature is expressed most clearly in the paradox of verses

three and four. While verse one tells us that creation declares the glory of

God, verse three follows up by clarifying that however this “declaration” goes

forth, it is without words. The “speech” of the book of nature “pours forth”

and “goes out through all the earth” but “is not heard.” What can this mean? Galileo

resolves this trouble by positing a “mathematical language” of the book of

nature, which perhaps resolves the paradox of how a voice can go forth into all

the world and yet remain unheard – mathematics is not an aural language.

But

following Galileo here is unsatisfying, for the brute imposition of a

mathematical solution on a poetic tension strikes me as exactly the kind of “repugnancy”

in interpretation that Thomas Cranmer exhorts us to avoid.[2]

The greater

problem with Galileo’s solution to the paradox of Psalm 19 is that as modernity

progressed, natural philosophers and scientists found that their discourse increasingly

left no room for God either as a premise or a conclusion. God was pushed to the

gaps, and eventually hunted out of those gaps as humanity became more and more

adept at explaining the mathematical relations undergirding the various natural

phenomena of the world. While I in no way want to deride scientific progress, I

do enjoy electric lights, computers, automobiles, vaccines, and all the rest, I

do want to note that scientific description has not lent itself well to sustaining

the kinds of poetic statements we find in the first six verses of Psalm 19. It

is rather difficult to speak of God appointing a tent for the sun from which it

emerges like a strong man to run its course with joy across our skies when we

know that the sun is a giant ball of burning gas around which the whole solar

system revolves. Scientific description, as emancipatory and liberating as it

has been for human flourishing, has also tended to be reductionistic, producing

a form of speech that a former professor of mine referred to as “nothing

buttery.”

The

propositions of “nothing buttery” are best exposed by a thought experiment:

Imagine that

we have gone to the WSO to see a performance with a bunch of scientists from

various specialities. Afterward, each scientist is asked to explain, according

to their field, what they observed. A sociologist might say something about how

music performances are “nothing but” the complex social dynamics and power

relations at play between performers and the audience. The evolutionary psychologist

may interrupt by pointing out, that, of course, what the sociologist saw as

emergent social phenomena, are “nothing but” various psychological frameworks

that prime us to be receptive to authority, repetitive noise, etc., all handed

down from various stages in our evolutionary development. At which point, the

neurologist jumps in to explain the latest study on how the psychologist’s

explanation is “nothing but” an elaborate way of commenting on how the physical

structures of our brain determine our response to musical performances. The

chemist snickers, and kindly sets everybody straight about how our perception

of music is really “nothing but” various chemicals that are washing over our

brain making it respond x to every y stimulus. Finally, the physicist can’t

take it anymore and declares them all fools for not understanding that music is

“nothing but” the vibration of particles in certain specified ways.

And so it

would go, each specialist accurately describing the observable phenomena from a

designated vantage point, yet none of those descriptions really captures the

sublime aesthetic experience of watching the WSO perform. Of course real scientists

are people too, and would probably not actually describe their experiences that

way, but in reaching for other, perhaps poetic, language to describe their

experience of the natural world, have they not strayed from exactly the kind of

discursive space that Galileo sought to preserve in order to secure the

integrity of a close reading of the book of nature?

The turn to

poetic language in relation to the book of nature is a move we see within psalm

19 itself, with its wonderfully self-deflecting metaphors that invite the

reader into a contemplation of the created world by resisting our attempts to reduce

such contemplation to propositions in the language game of “nothing buttery.”

We have

arrived today in a world where we have become quite adept at reading the book

of nature, yet no longer conclude that it says anything to us about even an

ambiguous deity. We live in what Charles Taylor calls, the immanent frame. In

the immanent frame, stars are just stars. They are nothing but burning balls of

gas. They make no declaration about transcendentals like the glory of God. Yet,

I know few people who can sustain that frame for themselves on a warm summer

night at the lake where the entire Milky Way is on full display. On such nights,

it seems as if we must be reminded that what we are seeing is not the glorious

work of God’s hand, but rather the leftover light of a million suns that have

already burnt out. On nights like that, we doubt the immanent frame, and in

those moments of doubt we long for the ability to read Psalm 19 truthfully.

I mentioned

earlier that Psalm 19 has three linguistic moments, and yet I have only really

spoken about the first one so far. Perhaps it is because, as someone who

resides firmly in the immanent frame, I find it hard to hear the speech pouring

forth from the creation that speaks to the glory of God. Yet, we shouldn’t be

surprised by that, for, as I pointed out, the paradox of this passage is that

this speech is voiceless – it is, in fact, not heard.

The language

of the book of nature is not heard precisely because the book of nature cannot be

read in isolation from God’s other book. The attempt by both the Council of

Trent and Galileo to make the reading of these books a professional endeavour,

to protect against potential misinterpretations, contributes to the setting up of

the immanent frame we now live in. This is precisely because what we are doing

is making this “reading” a matter of method which we can perfect without

reference to the one who is performing the speech-acts that bring these books

into being from beyond the order of creaturely reality.

To attune

ourselves to the divine self-disclosure is to recognize the mode by which God

has acted to create, sustain, and be in reconciled relationship with everything

that is. Rowan Williams has noted that our very ability to grasp and understand

the natural world is itself a graced reality of God’s economy toward us.

Williams writes, “There is never a confrontation between those two mythological

entities of modern epistemology – the innocent receptacle of the disinterested

mind and the uninterpreted data of external reality. The mind is itself already

an agency with a 'shape', a tendency to respond thus and not otherwise; it

makes patterns of what it confronts according to the patterning it has received

in its primordial contact with God's agency.”[3]

According to

Psalm 19 then, the speech that is not speech which declares God’s glory to us

is a product of our linguistic production precisely because what ontologically

precedes this linguistic activity is the second linguistic moment of the Psalm,

the revelation of God in his holy laws in the book of scripture.

To get a

sense of how this works, recall our Old Testament reading from Nehemiah chapter

eight. After Israel’s return and restoration from exile, the whole nation

gathers to read aloud the law, and the elders of Israel give interpretation to

the people along the way as they seek to reclaim their status as a people. What

is striking about this passage is that the Israelites understand that their

status as a people who can interpret the text is predicated upon the history of

God’s mighty saving work toward them through his covenant faithfulness. This is

made clear in the way the passage locates the reading of the Law among long

lists of names of people who represent the clan and kinship bonds of nationhood

that make up the covenantal history of a people who have been formed,

sustained, and redeemed by a God who is actively working in the world through

particular covenants with a particular people, that is, Israel.

The history

of the God who is at work in the world is the subject of the book of scripture,

and it is this book that the second linguistic moment of Psalm 19 attends to.

While verses seven to ten are beautiful descriptions of the law, it is verses

11-13 that I want us to attend to:

Moreover by

them is your servant warned;

in keeping them there is great reward.

But who can detect their errors?

Clear me from hidden faults.

Keep back your servant also from the insolent;

do not let them have dominion over me.

Then I shall be blameless,

and innocent of great transgression.

in keeping them there is great reward.

But who can detect their errors?

Clear me from hidden faults.

Keep back your servant also from the insolent;

do not let them have dominion over me.

Then I shall be blameless,

and innocent of great transgression.

Notice how the

reading of the law, the precepts and stories of a God who is at work in

history, is a formative force on the life of the psalmist? By the teaching of the book of scripture, the psalmist

is being cleared from hidden faults, made blameless, and kept from being dominated

by the insolent. In other words, in the book of scripture the psalmist is

introduced to the one whom Rowan Williams calls the ‘illuminating intellect.’

According to Williams, “Every human subject is in touch with the 'illuminating

intellect', the reflection of God's formative mental activity within our own:

below the surface of human mental agency… lies a kind of participatory

awareness, a contact not yet expressed in word or concept, that resonates with

the patterns of God's action in the created world. 'Spiritual forms', concepts,

intelligible patterns in our apprehending of the world, are the result of the

intellectual action of God drawing and moulding our mental action so as to

generate coherent images that encode or even 'embody' the rhythms of God's

working.”[4]

It may be that this “participatory awareness” is what we encounter on those warm

summer nights at the lake, under the stars, that causes us to doubt our own

immanence, suggesting that there might be cracks in the silence of nature to

something beyond the edge of words that sounds something like the glory of God.

Psalm 19,

through its depiction of the two books of revelation thus gives us an idea

about the relationship of these two books. The book of scripture tells us about

the God who has rhythms of work in the world that we can then expect, and indeed

do, encounter in the book of nature.

Conclusion

The book of

nature, such as it is, is without speech, its voice is not heard. But there is

one who speaks. That one is the same who, in our gospel reading, stood in the

synagogue and declared that he is the promised one of whom Israel spoke. That

one, is Jesus of Nazareth. We can perhaps affirm with Galileo that the book of

nature is, in fact, written in the language of mathematics, and indeed, we have

learned much from that book by better learning that language. But in reading

the book of nature that way, we have lost the ability to say with the psalmist

that the heavens declare the glory of God. In our secular age, the heavens are

silent, their voices are not heard. Yet as Catherine Pickstock has observed, “Silence

is not the last word, but shares penultimacy with utterance…”[5]

Perhaps the silence of our immanent frame, our inability to hear any songs from

the stars is ultimately the counterbalance to our own speech. The prayer of the

psalmist is that his speech, a creaturely product and ultimately a part of the

book of nature, would be acceptable to the God who has spoken and revealed and

acted in our world of space and time in the person of Jesus. The silence of our

immanent frame is the punctuation necessary for our creaturely speech to

respond to the forms of intelligible ordering that I have alternately called

mathematics, language, and God’s rhythm of work. The tension created between

the speech and silence of the book of nature brings us to the very edge of what

our

language is able to do and

calls us to recognize that the nature of our existence is as creatures who are

spoken by the Word before we ever speak. Our particular situatedness in the

tension between silence and speech is the place where God stands up and speaks

saying, “today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.”

Amen.

[1] Galileo Galilei, Online, http://inters.org/galilei-madame-christina-Lorraine

[2]

Article of Religion, XX.

[3]

Rowan Williams, “Grace, Necessity and Imagination: Catholic Philosophy and the

Twentieth Century Artist - Lecture 1: Modernism and the Scholastic Revival,” http://aoc2013.brix.fatbeehive.com/articles.php/2104/grace-necessity-and-imagination-catholic-philosophy-and-the-twentieth-century-artist-lecture-1-moder

[4] Rowan

Williams, “Grace, Necessity and Imagination: Catholic Philosophy and the

Twentieth Century Artist,” Lecture One

[5] Pickstock,

“Matter and Mattering,” Modern Theology, 31:4,

614.

Comments

Post a Comment