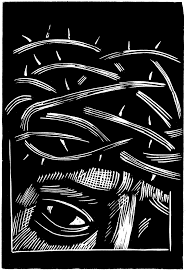

"Father, forgive them..."

Christ’s

first word from the cross, and indeed, his first word to us, is “Father,

forgive them, for they know not what they do.” At first glance, this appears as

a word of comfort. We are so ignorant of the ways we need saving, yet

mercifully, Jesus offers us forgiveness and makes everything alright. But if

this is all this word is saying to us, then the cross has been sanitized,

sentimentalized, and stripped of its narrative passion in the name of a good

atonement theory. As Stanley Hauerwas observes, “...as soon as these words from

the cross are bent to serve our needs, to give us a god we believe we need, it

is almost impossible to resist entertaining ourselves with speculative readings

of Jesus’s words from the cross. For example, we think what a wonderful savior

we have in Jesus, who, even in his agony, kindly offers us forgiveness”

(Hauerwas, Cross-Shattered Christ,

15).

The

error in such a reading is a grammatical one. On this reading the objects of

divine forgiveness, the vague prepositions of “they” and “them,” have taken

precedence over the subject, the definite person of the Father. Furthermore, it

is not at all clear in the text to whom the “they” or the “them” are referring.

Is it the criminals crucified on either side of Jesus in the preceding verse?

Is it the people and their rulers who stood beholding? Is it the imperial

soldiers who nailed him there and gambled for his clothing? Is it even,

perhaps, us? The text refuses to say. The ambiguity of reference for this verse

is precisely the point. This text is not about us, it is about the one whom

Jesus names from the cross - God the Father.

It

is extraordinarily tempting to make this text about us, for surely it is our

sin that needs forgiving, and if it is our sin, we must know something about

it. Certainly, if there is anything we know for sure, it is who we are and what

we do. We are constantly sure that if we can be certain about anything, it is

our own truth, our own authentic self-knowledge.

Again,

the text corrects this error in our thinking. We do not know what we do. We

don’t even know who we are. Are we criminals? Are we agents of empire? Are we

onlookers? But here I am, making this text about us, and our problems, even

though the text refuses to either identify a “them” or name a problem. Jesus

speaks positively only of his Father and the forgiveness that comes from him.

But

what is this forgiveness? Surely forgiveness need only arise in response to a

problem, a problem we normally call sin. Forgiveness deals with this problem of

sin. This neat way of articulating it, the problem and the solution, lands us

right back into the realm of theory once again and the comforting certainty

that we know what we are talking about.

Christ’s

first word to us from the cross is not a message about something certain that

we might call the “human condition.” It is the beginning of the exposition of

the cross and the God who hangs there. The grammar of Christ’s word, “Father,

forgive them, for they know not what they do” is the great reversal of our

alleged self-knowledge. The supposed word of comfort, “Forgive them” becomes a

withering word of judgement. The offer of forgiveness reveals precisely how

deeply we do not know what we are doing. It is because we do not know who we

are and what we are doing that we must look up and see Jesus on the cross and

there discover the nature of who we are and what our problem is.

The

Father’s forgiveness is first a word of condemnation. It is grace, to be sure,

but it is a withering word of grace. On occasion situations arise where a

person may have an encounter with somebody, after which they feel slighted. The

perpetrator of the slight may or may not be aware of having done anything

wrong, but if the victim of that slight offers a word of forgiveness, it is at

that moment that the perpetrator must come to terms with the reality of their

guilt. To accept the offer of forgiveness is to accept the guilty verdict. If

the perpetrator accepts the verdict, they may do so in the form of repentance.

The Scottish

theologian, James Torrance (Worship,

Community, and the Triune God of Grace, 54-5), following John Calvin (Institutes, III, 3, iv), makes a

distinction between this form of repentance which he names “evangelical

repentance” and another form of repentance, called “legal repentance.” Legal

repentance is the way many of us intuit repentance, people know they have done

wrong, they repent of their wrong-doing, and the repentance triggers the

mechanism by which they may be forgiven. Evangelical repentance, on the contrary,

begins with forgiveness. This forgiveness brings with it the knowledge of

guilt, the acceptance of this guilty verdict is repentance. In the former we

know what we do and are the authors of our forgiveness, in the latter, grace

defines us and subverts our attempts to take control of the world.

And so,

we begin to understand how Christ’s word from the cross holds together. The

word of forgiveness is not the answer to our problem of not knowing what we do.

The word of forgiveness is precisely the revelation that we do not know what

we do. But insofar as it is a word of forgiveness,

we are not left condemned with the knowledge of our own ignorance and

malfeasance. Therefore, the first word from Christ is the word of forgiveness,

not to comfort us at the sight of a tortured and dying God, but to reveal to us

the truth of what is being done on the cross. The word of forgiveness, as an

act of judgement and mercy, discloses to us the truth that on this cross, in

the body of this man Jesus, the judge has been judged in our place.

Ultimately

then, Christ’s first word to us from the cross, becomes a word for us, not

because it is primarily about us, but exactly because it is about him. Hanging

from the cross, Jesus takes our place as the guilty one, and from that

position, reveals to us our guilt by mercifully taking it upon himself. This

first word from the cross, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they

do” opens our meditations on the cross by mercifully disciplining us in our

ignorance and revealing to us that in Christ the great reversal has been

completed. We may not know who we are or what we do, but we do see Jesus, and

as we look on, hearing his words to his Father from that great height, we

discover that there is one who knows who and what we are, just as he is known

by the Father, and so, we are forgiven.

Comments

Post a Comment